In this article, originally published by RACGP, following my representative role on the 2018 Senate inquiry into transvaginal mesh implants, I write about the outcomes of the inquiry, and what they mean for GPs and their patients.

———————-

The Senate Community Affairs References Inquiry report, ‘Number of women in Australia who have had transvaginal mesh implants and related matters’ was released earlier this year and was damning of the implants, their manufacturers and many of the medical professionals who recommended and inserted them.

The aftermath of the inquiry will have a number of consequences for GPs and their patients who have suffered from the insertion of transvaginal mesh.

How the outcome of the inquiry will impact future treatment options

As of 4 January in Australia, transvaginal mesh that is solely used for pelvic organ prolapse via transvaginal implantation has been removed from the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). The other product withdrawn is the mini-sling.

The belief is that the benefits of inserting mesh for pelvic organ prolapse do not outweigh the risks posed to patients.

The current position for women with stress urinary incontinence is that synthetic mid-urethral sling (MUS) surgery is considered a relatively safe procedure with low complication rates when performed by a specialist surgeon. Other options to consider include the autologous fascia pubovaginal sling, Burch colposuspension, although these last are considered more invasive than MUS.

Launching into surgery without exploring other interventions should be avoided. The consent process needs to be clearer and the path to surgery involving the introduction of foreign bodies will need to be properly discussed with the patient, with risks and benefits outlined.

There is also a range of more conservative methods of symptom management that can be used prior to surgery. For example, an important management step is referral to pelvic floor physiotherapy or continence therapy with or without medication and vaginal devices, especially for women with stress urinary incontinence. Many women will also benefit from intravaginal pessaries, oestrogen creams and pelvic floor strengthening and retraining.

For women who have pelvic pain, education of doctors – from GPs to surgeons – in the causes of pelvic pain, urinary incontinence and dyspareunia will now include asking about previous surgery, and transvaginal mesh or urethral slings specifically.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is working to improve the criteria for qualification of new products and will require more stringent testing and research to confirm safety. The plan is for all devices to be registered and trackable through a central database in case of complications.

All revisions and complications should be reported to the TGA, the process of which has been simplified for doctors to easily log in and report adverse events (refer to TGA Incident Reporting and Investigation Scheme).

How GPs can approach treatment of affected women

GPs need to be mindful that women who have had mesh inserted and are exhibiting symptoms need to be listened to, taken seriously and have a physical examination of their abdomen, pelvis and vagina. A pelvic ultrasound is required, as well as referral to a gynaecologist or urogynaecologist.

Complications of slings that should be considered can include:

- urethral obstruction

- urinary infections

- pain

- neurologic symptoms

- pelvic organ perforation involving bladder, vagina, urethra, bowel

- mesh exposure erosion and extrusions through vagina, bladder and urethra

- fistulae.

What GPs should know about treatment of women who experience pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence

Stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse are different conditions, although both can be present in the same woman. Each requires separate assessment, and detailed assessment of each condition is required to be documented and measured in patient notes. Surgery for the two conditions may be performed concurrently.

Red flags for stress urinary incontinence include:

- recurrent incontinence

- debilitating severe incontinence

- incontinence associated with pain

- haematuria

- recurrent infection

- neurological symptoms or conditions

- patients using medications that cause an atonic bladder

- voiding dysfunction

- pelvic irradiation

- radical pelvic surgery

- suspected fistula

- significant pelvic organ prolapse

- primary nocturnal incontinence

- nocturnal enuresis

- significant post-void residual volume.

Red flags for pelvic organ prolapse include:

- stage 3 and stage 4 prolapse

- pelvic pain

- radical pelvic surgery

- pelvic irradiation

- suspected fistula

- pelvic mass

- other significant pelvic abnormality

- impaired renal function

- recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI)

- abnormal vaginal bleeding, post-coital or post-menopausal bleeding.

Resources for healthcare professionals and affected women

The Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care (ACQSHC) has worked with doctors, consumer representatives and the TGA to produce information sheets that will assist patients, GPs and specialists in evaluating symptom severity, making treatment choices, and understanding the treatment pathways available and how they may lead to certain outcomes.

The Continence Foundation provides support and information regarding transvaginal mesh to women throughout Australia.

Originally published: racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/transvaginal-mesh-implants-inquiry-what-gps-need

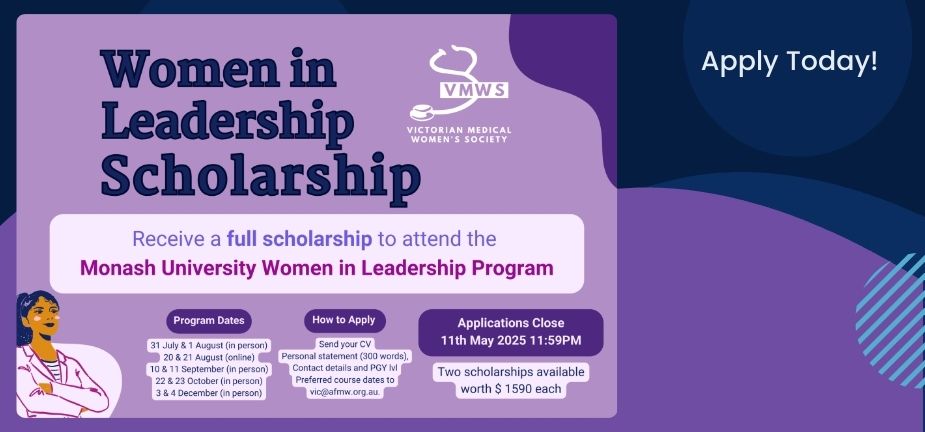

Associate Professor Magdalena Simonis AM is a Past President of the AFMW (2020-2023), former President of VMWS (2013 & 2017-2020) and current AFMW National Coordinator (2024-2026). She is a full time clinician who also holds positions on several not for profit organisations, driven by her passion for bridging gaps across the health sector. She is a leading women’s health expert, keynote speaker, climate change and gender equity advocate and government advisor. Magda is member of The Australian Health Team contributing monthly articles.

Magdalena was awarded a lifetime membership of the RACGP for her contributions which include past chair of Women in General Practice, longstanding contribution to the RACGP Expert Committee Quality Care, the RACGP eHealth Expert Committee. She is regularly invited to comment on primary care research though mainstream and medical media and contributes articles on various health issues through newsGP and other publications.

Magdalena has represented the RACGP at senate enquiries and has worked on several National Health Framework reviews. She is author of the RACGP Guide on Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery and co-reviewer of the RACGP Red Book Women’s Health Chapter, and reviewer of the RACGP White book

Both an RACGP examiner and University examiner, she undertakes general practice research and is a GP Educator with the Safer Families Centre of Research Excellence, which develops education tools to assist the primary care sector identify, respond to and manage family violence . Roles outside of RACGP include the Strategy and Policy Committee for Breast Cancer Network Australia, Board Director of the Melbourne University Teaching Health Clinics and the elected GP representative to the AMA Federal Council. In 2022. she was award the AMA (Vic) Patrick Pritzwald-Steggman Award 2022, which celebrates a doctor who has made an exceptional contribution to the wellbeing of their colleagues and the community and was listed as Women’s Agenda 2022 finalist for Emerging Leader in Health.

Magdalena has presented at the United Nations as part of the Australian Assembly and was appointed the Australian representative to the World Health Organisation, World Assembly on COVID 19, by the Medical Women’s International Association (MWIA) in 2021. In 2023, A/Professor Simonis was included on the King’s COVID-19 Champion’s list and was also awarded a Member (AM) in the General Division for significant service to medicine through a range of roles and to women’s health.